INTERVIEW

INTERVIEW

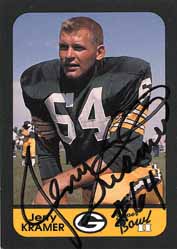

Jerry Kramer, Green Bay Packers and SHS football star

By Billie Jean Plaster

Sandpoint High School made a bit of football history last fall when the Bulldogs captured their first state high school football championship. Two months later, the Green Bay Packers lost one of the most hotly contested Super Bowls ever to the Denver Broncos.

Strangely enough, there's a bit of a thread that ties Sandpoint and the Green Bay Packers together. The thread's name is Jerry Kramer, an SHS alumnus who went on to a long career with the Packers during the 1960s under legendary coach Vince Lombardi. In 1969 Kramer was named the outstanding guard of the first 50 years of football by the National Football League. And he's a contender for induction into the Professional Football Hall of Fame.

But before he was a Packer, Jerry Kramer was a Bulldog. He played four years at Sandpoint High under Coach Cotton Barlow, who first assigned him to that obscure position without limelight, right guard, as well as kicker. He graduated in 1954 and went on to play football at the University of Idaho in Moscow on a scholarship. He was picked in the fourth-round draft by the Green Bay Packers in 1958.

His first professional football season was by most standards dismal. The Packers had the worst season in their then 40-year history: 1-10-1. But Jerry didn't care. To him it was an incredible year; he was playing professional football on a $7,750 contract with a $250 signing bonus, and he was on Cloud 9.

Then Lombardi took over as head coach in 1959. The Packers hadn't won a title since 1944; but under Lombardi the team won NFL championships in 1961, '62, '65, '66 and '67, the last two years being Super Bowls I and II. They are the only team to win three championships in a row; in fact, thanks to those years the Packers today hold more NFL titles than any other team.

In his 11-year career with the Packers, Kramer was voted All-Pro five times and went to the Pro Bowl three times. After retiring from football in 1968, he got into writing and making films. Among his other books, he wrote Instant Replay, a diary of his 1967 season with the Packers, and edited by Lombardi: Winning Is the Only Thing, published shortly after Lombardi died in September 1970. He also produced "The Habit of Winning," a motivational video.

Twice divorced, he now lives in a sprawling house on the outskirts of Boise. He's the father of six children, two of whom, Jordan and Matt, will be playing at the University of Idaho this fall on football scholarships.

Today, at 62, Kramer is president of Single Source Telecommunication, a payphone outsourcing company. He also spends time on a variety of charity events. At 6 foot, 3 inches, he is still at his playing weight of 250 although he quips, "It's just redistributed."

His scars are still there, too, an interesting collection that might make him seem accident prone. His proclivity for trouble even struck on the morning of our interview, when he gashed his right ring finger on the stem of a broken glass. Hardly missing a beat as his finger bled, he let me proceed to tape our interview.

Q. How would you describe your childhood in Sandpoint?

A. We were inside the city limits by half a block. We had a big garden, a cow and a calf. Occasionally we raised a pig. Charlie (his father) loved to have a big garden, and he'd have us hoeing that sucker all summer long and pulling weeds. My two huge complaints as a child were working the garden and milking the cow.

What are some of your better memories of growing up in Sandpoint?

We had some wonderful times at the beach. I loved the hills, loved the fishing, especially over by the GN tracks on Berry Creek. We didn't have any of the video games or TV or anything like that, so our entertainment was the other kids. There was a vacant field right across from the house where we played ball and had all kinds of fun. Our folks didn't have much money, but no one else seemed to, either. Charlie was doing all right in the business. ... He did well, worked hard, worked long. He was kind of a 'Nazi' Christian. He believed in church, and we went to Sunday School every Sunday or we got our butts whipped. He practiced the wisdom of the day, "Spare the rod, spoil the child."

What got you started thinking seriously about football?

There were two incidents that had a pretty big impact on me. We got a college coach from the University of Idaho named Babe Kurfman who was up talking to some of the seniors, probably George Eidam, and he came over and patted me on the shoulder and said, "You're the kind of boy we'd like to see at the University of Idaho." So that was a huge thrill and huge honor to be tapped by the big coach. And we had a line coach by the name of Dusty Kline who was an older guy who had been around quite a bit and was kind of semi-retired but was coming out and helping coach. He took me aside one day when I was a sophomore and started commenting about the size of my hands and my quickness and strength. And then he looked at me and said, "You can if you will," and then he turned around and walked away. And I'm going "Can what? Will what? What the hell do you mean?" And it took me quite a while to figure out what he was saying, but he was saying exactly the right thing. If you have the capability, if you have the mind, if you put the willpower and effort behind it, you can if you will.

You were coached by Cotton Barlow, who by Sandpoint standards was a legendary coach. Then, of course, you were coached by Lombardi. How would you compare them?

There's a lot of similarities, actually. Both serious, both committed, intense. Cotton could get so involved in what he was doing, he would lose himself. Coach Lombardi would kiss one of the coaches goodbye instead of his wife. He was so wrapped up in himself. He'd leave the house with his pants unzipped, and all kinds of things. Both were strong believers in conditioning and execution. Cotton was a strong believer in motivation. We played Kellogg in Coeur d'Alene because their stadium had burned down. They were going to charge our band 50 cents a head to get into the game. Cotton used that to get us so angry. He got us so mad at Kellogg, that we went out and beat them like 55 to 7, just beat the hell out of them. When you think about it later, you go "Who gives a damn about the band, really?" Both understood motivation.

When you wrote Distant Replay in 1984 you said the most important lesson you learned from Lombardi was to do things right all the time. Were there other lessons?

Yeah, that's probably pretty strong and pretty consistent. He was the kind of coach who could see a gap between where you were and who you could become. ... He felt that it was his God-given responsibility to close that gap. Make you use all your talent and all your abilities, every ounce of it. And the more talent you had, the more he wanted it. So, first of all, he made us aware of that gap as football players and then later on as human beings. There's a constant journey, a constant learning, a constant process of growth and maturity and wisdom, and the whole thing never stops. I don't think you ever close the gap. You get closer to closing it, but if you continue to grow for a lifetime, then you've had a wonderful life, a wonderful journey.

Probably one of your most famous moments in football came in the Ice Bowl in 1967 the block that let Starr make the last-second winning touchdown.

The game is a great memory. The block was just another moment in a long series of wonderful moments. Probably my introduction into the College All Star Game at Soldier Field in Chicago was one of my great thrills in football. It was a night game and they turned out all the lights in the stadium ... and put a spotlight on you as you ran through the goal posts and out to the middle of the field. We played the Detroit Lions, and we beat them, which was pretty unusual for a college team to beat the pros, the world champs. The game was just electric. It was so exciting, you could hardly breathe. Then I had a chance to kick three field goals in Yankee Stadium in the '62 world championship game. We won 16-7, and my last field goal sealed the victory. The team just swarmed around me, just piled on me, hugging, clapping, yahooing and celebrating. For a lineman, that was rare to be the guy who made the difference in the victory.

You've said that writing Instant Replay helped you have a better football season. When you wrote Distant Replay, did it have a similar effect for you in your life after football?

It made me appreciate two things a great deal more than I had before. It made me appreciate the closeness of the team. Several of the guys told me they loved me. A big black man, 360 pounds: "I love ya, Jerry." I'm not used to that. I'm not used to any man telling me they love me. That was Bob Brown and Lionel Aldridge and Herbie (Adderley). The depth of the emotion that we felt, I felt, but I didn't realize everybody felt it, and I didn't realize it would be that strong 18, 20 years later. The impact that Coach Lombardi had surprised me. I expected some of the guys to say that he had an impact on their lives, but Herbie said it when I asked him if he thought about Coach Lombardi and he said, "Every day of my life." I love my father, who's also deceased, but I don't think about him every day of my life, but I think about Coach Lombardi every day of my life.

Recently, a couple of your former teammates, Ray Nitschke and Lionel Aldridge, died. How did their deaths affect you?

Lionel was not a surprise. He was having thyroid problems, and he was 360 pounds ... so it wasn't a surprise that Lionel passed. (Sighs deeply.) Ray was a shock. Ray made me flinch. Ray hit close to home. He was in my rookie class. He and I played in the College All Star game together. We were months apart in age. We played together for 11 years, all of my career. We were friends. I had grown to really like Raymond and respect him and think highly of him. There are a lot of similarities between Ray and I. We both matured and had grown a lot as we traveled down the road. That one struck a lot closer to me.

Many of your former teammates have been inducted into the Professional Football Hall of Fame, but it's an honor that's eluded you so far. Why do you think you haven't been elected yet?

I really don't have an answer for that. I had a lot of recognition and a lot of accolades. ... There were 17 guys on the NFL 50th anniversary-year team, and 16 of them are in the Pro Football Hall of Fame, and yours truly has been nominated 10 times, which is a great honor and a great thrill. It wouldn't be right to be upset or angry or disturbed because you didn't get one honor when you've been given so many. So I refuse to get negative about it and feel bad about it. ... I can't imagine my life changing a great deal because I got selected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame. My life is about like I want it. It's organized around the people and places that I want it, and I don't think it will change it one lick.

You talk about you and your teammates having "Ps.D." degrees poor, smart and driven. With all of your success, your own kids haven't been deprived of much. Have you been able to put that fire into them?

That's a problem, because deprivation is a great motivator. But I've tried to overcome that with positive reinforcement. I find that a positive statement goes a long way at the right time. ... That's what I try to do with them to overcome things being too easy for them. Lombardi was that way, too, and I didn't understand it until 10 or 12 years ago, when I started to understand positive motivation.

Is there anything else you would say?

It's just a little strange to still be a football player at this particular point in time. You think you get over that football business a long time ago, but it won't leave you alone. It's pleasant and not much of a problem. The whole experience is so much more than I ever anticipated. Football's opened some interesting doors.